What's good and bad depends on trajectory, not just territory

|

The previous page gave a simple overview at what's good and bad for the offense. To be precise--and this is not too much information for a basic look at baseball--we have to understand the terms fair ball and foul ball.

Start by considering the batter standing at home plate trying to hit the pitched baseball into fair territory, which spreads out from him like a slice of pie. Under the original rules he was allowed to try to advance around the bases as long as the batted baseball touched fair territory sooner or later. But there are two problems with this. First, batters often hit baseballs that then bounce from fair territory into foul territory (and vice-versa, which is much less frequent). In fact, batters used to do this on purpose. Nine defensive players weren't enough to cover all that ground. Second, batted baseballs sometimes fly so far and high beyond the playing field--all the while on a curving trajectory--that the umpire(s) can't judge where they land in relation to a foul line. So now the distinction between a fair ball (possibly good for the offense) and a foul ball (almost always not good for the offense) is based on the path that the baseball takes with reference to not only the foul lines, but other markings: the bases and the foul poles.

|

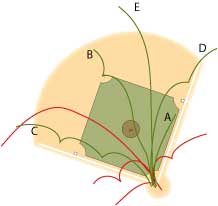

| Diagram 3: Green represents

fair balls Red represents foul balls |

A (batted) baseball is fair if:

- it stops in fair territory before it reaches first or third base (A), or

- it hits a base (B), or

- bouncing or rolling, it passes first or third base on or above fair territory (C), or

- it passes first or third base in the air and makes its first bounce in fair territory (D), or

- the baseball is hit so far that it leaves the playing field between the foul poles or hits one of them (both of which types of events are very good for the batter) (E) or

- the defense touches it while it is moving on or above fair territory.

A (batted) baseball is a foul ball in all other cases.

A fair ball allows the batter to at least try to advance to first base or beyond. Maybe he'll be successful, maybe not. On the other hand, a foul ball is usually bad for the batter and his team, although in some situations it's just indifferent. We'll discuss the basics of all this elsewhere.

Let's return to the diagram of the previous page, the simple view of the parts of the baseball field that the batter aims for.

|

| Diagram 2 |

Green and brown: now you know why we didn't say that baseballs hit there are always good for the batter. Their trajectory may make them foul balls, although this is not common.

Blue: on the other hand, blue is always good for the batter because a baseball that lands there could never be a foul ball. That is, it could never have left the field over foul territory (i.e., on the foul territory side of a foul pole) and then curved into the blue area. It would have broken the laws of physics.

Red: now you know why we can't categorically state that a baseball that stops there is always a foul ball. Once or twice a game, a fair ball bounces into foul territory next to or beyond first or third base.

Yellow:we're confident that a baseball that ends up there could not have taken the route of a fair ball. [hmmm ... not the way this diagram is drawn. A baseball could sure bounce from the green into the corner of the yellow that abuts the gray. Sorry about that. We'll get our artist to make the gray area bigger.]

Gray: baseballs that fly out of the playing field near a foul pole can easily curve into a gray area from either side of the pole. This is exciting because a fair ball that doesn't land until it reaches the stands is an automatic run for the batter and any other member of the offense who is occupying a base at the time: it's a homerun. And baseballs can bounce into the gray from either fair or foul territory. The former case allows the batter to proceed to second base. The latter case is just a foul ball. Both cases are covered elsewhere.